The Yoga Sutra (YS II.16) teaches that we should “avoid future suffering.” This means not only letting go of behaviors, attitudes or habits that cause us pain, but also looking ahead and preparing for difficulties that may arise so they can be avoided. This Sutra applies to our environment and its seasonal changes as well. They require our attention, so we can prepare and mitigate any adverse effects to come. After all, if we heard that a blizzard was coming, we would go to the store to buy our milk, eggs, and bread, and possibly batteries. We would make sure there was gas in the snowblower, we had trusty shovel, and maybe a little extra food for the birds.

I love autumn. The days may be warm, but the nights feel cool and clear. Mums, and pumpkins, and apples appear everywhere. And, we know that soon leaves will explode in dazzling reds, oranges, and yellow.

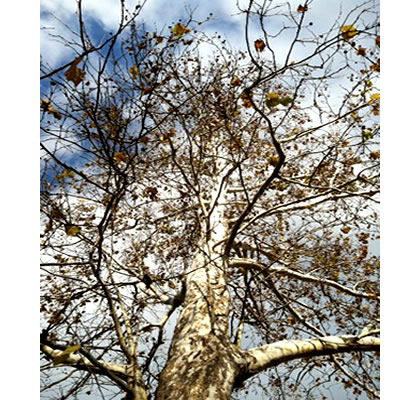

But some of the qualities of fall that we tend to overlook can cause problems. Think of the leaves we see fading. Their tips curl as they become drier and drier, even as many color magnificently. The leaves of most deciduous trees will fall to the ground, dry and crunchy as we walk in them. The air moves, as winds sweep the dried leaves, and the days begin to cool.

Ayurveda – the ancient Indian holistic medical system – tells us fall is the season when vata dosha is dominant. The word dosha means “a fault or mistake,” and vata means “to blow or move like the wind.” Vata is one of three doshas, the others being pitta and kapha, that are components of all life.

Throughout the year, each of the three doshas becomes dominant in different seasons. When vata dosha is dominant in fall, it can lead to an imbalance of that dosha within us. And, if we are in our wisdom years, we become more vulnerable to an imbalance of our vata dosha.

Some of the symptoms we might experience when vata is out of balance include: difficulty sitting still, racing thoughts. unfocused mind, difficulty sleeping, dryness of the skin, hair, or nails, constipation, forgetfulness, or anxiety. Our joints might feel creaky, as if they needed lubrication.

We may experience a vata dosha imbalance in seasons other than fall, depending upon our own constitution (the mix of the three doshas we are born with) and our diet, lifestyle, and life situation. But just to emphasize – the qualities of fall make us more vulnerable to a vata imbalance.

An ayurvedic practitioner can help us understand our own unique constitution and recommend dietary and lifestyle changes to help us achieve or maintain balance. Our yoga practice can help us mitigate the suffering that a vata inbalance can cause for our bodies, energy, mind, and emotions as we work to create a sense of groundness. We can use breathwork to calm our breath and mind; we can include a meditative practice to focus the mind. While we regularly use these tools in yoga, it is the intention of our practice that is most important. Bringing a calm, quiet, meditative intention to our yoga practice can help us maintain balance so we can welcome rather than suffer from the autumn days.

Let fall be a time to nourish yourself with your yoga and enjoy the season, and please let me know if you would like to work with me to develop your personal yoga practice for the fall.